The Treasury's Argentina Bet: Scott Bessent Claims a Profit, But the Data Tells a Different Story

There are two ways to look at the U.S. Treasury's recent intervention in Argentina. The first is through the lens of a political press release, where Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent can declare victory. The second is through the cold, hard lens of a currency trader's P&L statement. Bessent is pushing the first narrative hard, recently posting on social media that the "Argentine economic bridge has now turned a profit for the American people."

It’s a bold claim. And as someone who has spent a career scrutinizing financial statements, I find that when a claim is both bold and vague, it’s usually hiding something. The political objective was clear and, by all accounts, achieved. The intervention—a combination of direct peso purchases and a $20 billion currency swap line, which has been characterized as The US bet big on Argentina bailout—was designed to stabilize the Argentine peso ahead of midterm elections, shoring up support for President Donald Trump’s key regional ally, Javier Milei. Milei’s party performed well, strengthening his position. A political win, no doubt.

But a financial profit? That’s an entirely different proposition. Claiming a profit on a currency position without providing the entry price, the current mark-to-market value, or the size of the position is not an analysis; it’s a marketing slogan. The U.S. Treasury has become a black box, and we're being asked to trust the label on the outside.

A Gamble Against Gravity

Let’s be precise about what’s happening here. The U.S. Treasury, using taxpayer-backed funds, has taken a long position on an emerging market currency with a long and storied history of catastrophic devaluations. This isn't a typical central bank stability operation aimed at preventing global contagion. By the Treasury's own admission, this was a targeted move to support a political ally. It is, for all intents and purposes, a directional bet.

And the market fundamentals are screaming that it’s a bad one.

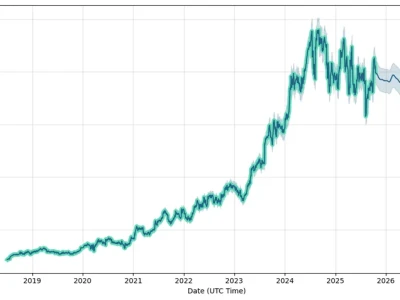

The Argentine peso has fallen roughly 30% this year. To be more exact, the decline against the dollar has oscillated between 28% and 32%, but the trend is unambiguously negative. A drop of 4% occurred in just the last month, after the U.S. intervention was in full swing. This is the market’s way of saying the currency is overvalued. It’s a classic scenario: a government is trying to hold a currency at an artificially high level, and the economic gravity is pulling it down. You can almost picture the tense silence on a trading floor in Buenos Aires, watching the central bank burn through its foreign reserves to defend a line on a chart that the rest of the world refuses to believe in.

This brings us to the central irony of this entire affair: Scott Bessent. The man made his name as a star currency trader for George Soros, famously participating in the 1992 speculation against the British pound. That trade was a bet that the Bank of England couldn't defy market gravity forever. They were right, and they were rewarded handsomely. Now, Bessent finds himself in the role of the Bank of England, standing on the other side of the same fundamental trade. Why would a man who knows this game so well take a position that looks, from the outside, like catching a falling knife?

The only logical answer is that the primary objective was never financial profit. It was a political bridge to get Milei through an election. The problem is, bridges cost money to build, and this one appears to be built over a financial sinkhole.

The Missing Ledger

The most troubling aspect of this operation is the complete lack of transparency. The Treasury has been conspicuously silent on the key data points needed to verify Bessent's claim of profitability. We don't know the timeline or the exact scale of the peso purchases (analysts estimate it could be as high as $2 billion, a figure that is more symbolic than market-moving). We don't know the average price at which those pesos were acquired. Crucially, we have no details on what, if any, collateral the Argentine government pledged to secure the $20 billion swap line.

I've looked at hundreds of sovereign debt and currency agreements, and this level of opacity from a G7 nation's treasury is highly unusual. It feels less like a state action and more like a private fund trying to keep its proprietary strategy under wraps. But this isn't a private fund; it's public money.

Without this data, Bessent’s claim of a "profit" is functionally meaningless. Did the Treasury buy pesos at the absolute bottom of a trading day and sell them hours later for a small gain? Perhaps. But that’s day-trading, not a successful long-term intervention. Is the "profit" a paper gain based on a momentary rally that has since been erased? Or is it calculated based on some obscure derivative structure we know nothing about?

This is where the skepticism of an analyst must kick in. The consensus among economists is that the peso is not, as Bessent has declared, "undervalued." It's being artificially propped up by Argentina's central bank, which is hemorrhaging its IMF funding and foreign reserves to do so. Argentines themselves are voting with their wallets, flocking to neighboring countries to spend their pesos where they still have some value. When the citizens of a country are telling you their currency is overvalued, it’s probably wise to listen. The question isn't if the Argentine central bank will be forced to devalue, but when. What happens to the U.S. Treasury's "profit" then?

A Trade Without an Exit

Ultimately, the Argentina intervention looks less like a savvy investment and more like a high-risk political maneuver with a financial component that was, at best, an afterthought. The political goal was met, but now the Treasury is left holding a depreciating asset, claiming victory while the numbers tell a different story. Bessent has two choices: he can "double down" and commit more U.S. capital to defending the peso, escalating a questionable bet, or he can quietly unwind the position, likely at a loss, and hope no one scrutinizes the final accounting too closely. The current strategy of declaring profit without providing proof suggests he’s trying for a third option: simply shaping the narrative and hoping the market turns his way. That’s not a strategy; it’s a prayer. And the market rarely answers them.